But what happens when clothing begins to take on a life of its own, to signify membership in a group or subculture that itself could imply certain attitudes, beliefs or political views? Sociologists call these "communities of style."

|

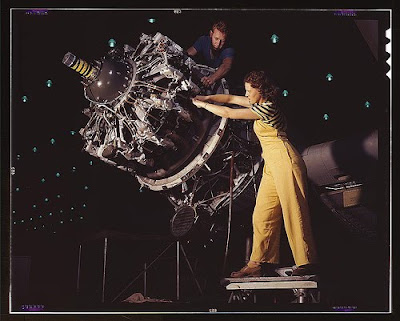

| Click to enlarge. From http://www.smithsonianconference.org/expert/clothing/ |

Smithsonian expert Diana Baird N’Diaye created this infographic to explain the idea of clothing as "the visual vocabulary of a community." Those communities can be colleagues or countrymen, Rocky Horror fans or supporters of a sports team. While some of these symbols and identifications are obvious, others depend on context, both for the viewer and the wearer. "Why do I wear my pants so low?" garners three possible answers: "You're imitating an inmate!" "My friends all do it!" and "It looks cool!"

Seventy years ago, similar answers could have been applied to young men wearing zoot suits, a surprisingly political slice of fashion history given close examination by Kathy Peiss in her book, Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style.

A "zoot suit" was characterized by a long jacket with sloping shoulders, paired with pants that were very wide at the knees and pegged in narrowly at the ankles. They came in bright, contrasting colors and were often paired with wide-brimmed hats over long hair and a very long watch chain at the waist.

The origins of the zoot suit are contested, but it's generally accepted that the trend was picked up in earnest and made popular among young African American men in Harlem in the 1930s, and popped up in large and small cities across the country, not only on African Americans, but also Filipinos, whites (especially swing dance enthusiasts) and especially Mexican Americans. A burgeoning community of young Mexican American men in Los Angeles, newly flush with cash in the early 1940s from military industrial jobs, spent their time in dance clubs, wearing these flashy suits and dancing. Peiss points out that "zoot suits could be controversial within these communities of color even before they became items that provoked fear and anxiety among white Americans. The style threatened African American and Mexican American community leaders, who insisted that respectable appearance and appropriate behavior would help secure the safety and status of these groups."

The War Production Board (WPB) tried actively to influence fashion styles to conserve on wool and cotton fabrics needed for military uniforms. It started by regulating against the second pair of pants that commonly came with suits, then cuffs, patch pockets and wide lapels - all elements that required more fabric to create. The idea of a narrow silhouette for men's and women's clothing was actively promoted as "patriotic" and written in to law. Production of the zoot suit style was specifically banned by the WPB in September 1942, rendering the style unpatriotic in some circles, but not all. Even the US Senate was divided on the issue, with some Senators backing up the WPB and others allowing that youthful fashion styles could not realistically harm the war effort. The production ban was difficult to enforce, and sales of the style continued and even increased, with the allure of forbidden fruit. Stores sold "back stock," advising customers to get the suits while they still could after production had been disallowed. Restrictions on cotton and wool shifted fabrication to synthetic fabrics like rayon, which also had the advantage of being available in ever-brighter colors.

By June 1943, the style's popularity had reached an all time high, and so had racial tensions in Los Angeles. Beginning on June 3, white sailors left military bases in Long Beach and elsewhere and headed into the city in search of young Mexican American men in zoot suits. Per Peiss, they "prowled the streets, searched nightclubs, and invaded movie theaters, forcing the managers to turn on the lights so they could identify youths by their attire. When they found a zoot suiter, they beat him, stripped him of his pants, and tore his jacket." Over the course of the next four days, they were joined by increasing numbers of civilians, targeting not only Mexican Americans but also some African Americans and Filipinos, and not all in zoot suits. By June 7, there were 5,000 people in downtown Los Angeles either looking for a fight or looking for one to watch. Police finally took action, but mostly by arresting Mexican American men, and military authorities kept servicemen on base and off the streets. By June 8 it was over, but only after more than 100 people had been seriously injured. No one died. Only two of the white servicemen were arrested.

The press began referring to these events immediately as the "zoot suit riots" and the moniker has stayed with them ever since. The zoot suit didn't cause the riots, but (as Peiss puts it) "the zoot suit became a material, tangible emblem, distilling the everyday encounters and cultural clashes of ordinary men into legible signs. . . . It had become a clothing style with political implications, which were recognized especially by the elites of Los Angeles but also, in no small measure, by the young men who were attacked for wearing it." Throughout the investigations that followed, police insisted that zoot suits had become a signifier of gangs and hooliganism, clearly communicating criminal intent. A grand jury disagreed, but the characterization was cemented in the press and the minds of the public. The style, now much more closely associated with crime, didn't die, but continued to evolve and even spread to resistance movements in Europe. By the 1970s, the term "zoot suit" was mostly historical, even as the style's descendants continued to be popular among Mexican Americans in particular.

When swing culture hit a revival in the 1990s, with the release of the movie Swing Kids, a widely seen Gap commercial featuring swing dancers, and albums by nouveau swing bands like the Brian Setzer Orchestra and Cherry Poppin' Daddies, zoot suits had a renewed cultural currency, especially with the popularity of the 1997 song Zoot Suit Riot. Suddenly, they were the most-requested item in vintage clothing stores (which shop keepers couldn't produce - very few 1940s era zoot suits survived). But aside from brief mentions of "sailors" in the song, the brutal historical context of the phrase was stripped, and a "zoot suit riot" came off sounding like a raucous party. So the zoot suit was adopted in a new community of style, mostly with connotations of romance and classy theme parties. No one expected our grandparents, the original contemporaries of the style, to be confused by the switch.

But the question "Why do I wear my pants so low?" and its many answers remain, as we were reminded at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival's program The Will to Adorn this summer.

Questions about baggy pants or zoot suits or hoodies can start to have serious, violent consequences - either in the moment or after the fact of violent confrontations. It has been remarkable to see commentary on the potential culpability of clothing in violence arise again in the discussions of George Zimmerman's shooting of Trayvon Martin, much as it did in the wake of the zoot suit riots. Robin Givhan put a fine point on this in her Daily Beast piece just a few weeks after the shooting:

Geraldo Rivera was lambasted for suggesting that a hoodie was as culpable in Martin’s death as the shooter. He later apologized for his remarks. But the fact is, we do like to play with our public image—pretending that it doesn’t matter and yet knowing full well that it does. Baggy jeans became popular among young men—whether honor-roll students or delinquents—thanks to all of their negative, subversive connotations. Walking up to the edge of propriety and stepping over the line are all a rite of passage to self-definition.But if Zimmerman had any accomplice in the shooting, it wasn’t a fashion faux pas, it was fear. And that fear was fueled by ignorance, bravado, misinformation, history, and even popular culture. Fear can make most anything seem threatening: even a black kid walking along with a bottle of iced tea and a package of Skittles. Hoodie or not.

The public outcry that followed the implication by Rivera and others that the hoodie was culpable, and the subsequent "hoodie protests" that saw scores of people marching in hoodies across America and even on the floor of the House, says that we have made at least some progress on this front. It's not just relatively dispassionate academic examinations of the case that say clothing cannot be culpable - the idea is now part of the broader public consciousness.

But we still wonder, "Why do you wear your pants so low?"